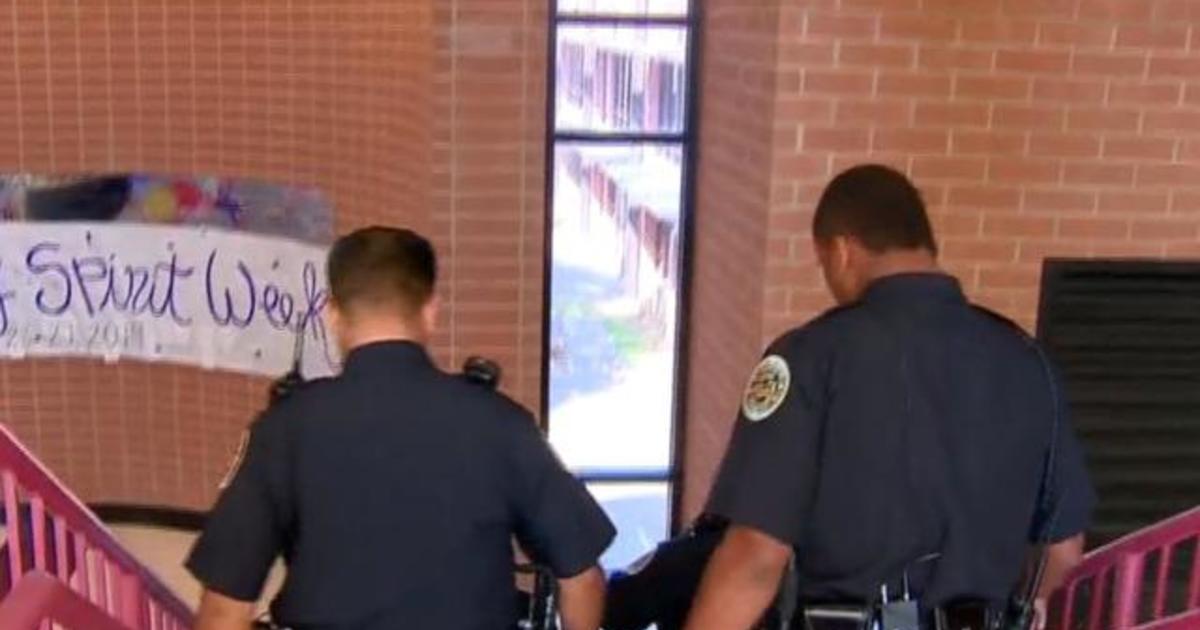

Many protesters demanding police reform have also drawn attention to the relationship between police and schools. More than 40% of public schools in 2016 had a school resource officer, who is a sworn law enforcement officer.

When 6-year-old Kaia Rolle threw a tantrum in class last year, she was arrested by Orlando police. A video from New Mexico shows a police officer tasing a special education student last year.

And a sheriff’s office in North Carolina fired a school resource officer last December who was seen on surveillance video body-slamming an 11-year-old student, a boy who weighed just 70 pounds.

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, Black children represent 35% of juveniles arrested despite only making up 15% of the youth population.

Dimitri Taing, a high school senior in Philadelphia who brought a pocket knife to school, said that mistake almost cost him his future.

“The cops took me in. I thought I was going to get arrested because that’s how it goes sometimes,” he told “CBS This Morning” national correspondent Jericka Duncan.

The school district paired Taing with a social worker instead of filing charges against him.

“They taught me how to stay out of trouble. Something positive. How to cope with things. They gave me some motivation,” Taing said. “And they directed me to the future.”

Just a few years earlier, the Philadelphia school district may have treated Taing very differently.

During the 2013-2014 school year, nearly 1,600 children were arrested for things such as fighting and bringing knives or mace to school.

But a diversion program started the following academic year by school safety chief and former Philadelphia Police Deputy Commissioner Kevin Bethel helped change that.

“Our school safety officers are not sworn Philadelphia police officers. They do not have the power to make arrests,” Bethel said.

Last year, there were fewer than 260 arrests, an 84% decrease from 2014.

“We’re able to partner with Department of Human Services, who run the juvenile programs in the city for the Juvenile Justice Programming,” Bethel said.

Instead of arresting a child for minor offenses, the school sends a social worker to the student’s home.

“Oftentimes, we find grandmothers who are raising grandchildren by themselves, and they’re struggling. Kids with no heat, no gas,” Bethel said.

Asked how identifying those issues at home changes the end result, Bethel said, “I’ve been in this space, in law enforcement, 35 years, … and I can’t tell you how rewarding it has been in my life, to be — for the first time — really feel like I’m giving service.”

“You really start to rebuild a lot of these young people,” he said.

Mo Canady, the executive director of the National Association of School Resource Officers, agrees with some aspects of Bethel’s approach.

“Police shouldn’t be in schools to police,” Canady said. “We should be in schools to do community-based policing, and that’s a whole different thing.”

Canady believes properly trained police officers have a place in schools, especially in the event of a shooting.

“Good SROs want to be the protector of that community,” Canady said.

But Senator Chris Murphy of Connecticut and Representative Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts argue police do not belong in schools.

“Police, especially in schools with majority students of color, end up putting these kids on a pathway to the criminal justice system,” Murphy said.

Murphy and Pressley have introduced the Counseling not Criminalization in Schools Act, which would establish a $2.5 billion grant program for schools to replace law enforcement officials with those that provide services that support mental health.

“We need to be making investments in social emotional wellness supports and restorative justice practices,” Pressley said. “It’s not a deficit of resource … It’s just been a deficit of understanding, a deficit of empathy.”

For Taing, if he had been arrested, he said his life would be “very different.”

“When you reach out to youth like me, they really, like, give out a spark of hope,” he said.

According to the ACLU, of the approximately 56 million students in the country, 14 million are in schools with police but no counselor, nurse, psychologist or social worker.

This year, districts in cities like Denver, Oakland, and Minneapolis severed their ties with police departments following the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis police custody.