In his 45 years in the supermarket industry, Marc Perrone knows of only two people who died on the job. This year alone, that figure has passed 100 as the coronavirus put food workers on the front lines of the pandemic. Overall, 35,000 members of the United Food and Commercial Workers union, which he leads, have either been diagnosed with COVID-19 or have family members who’ve fallen ill with the virus.

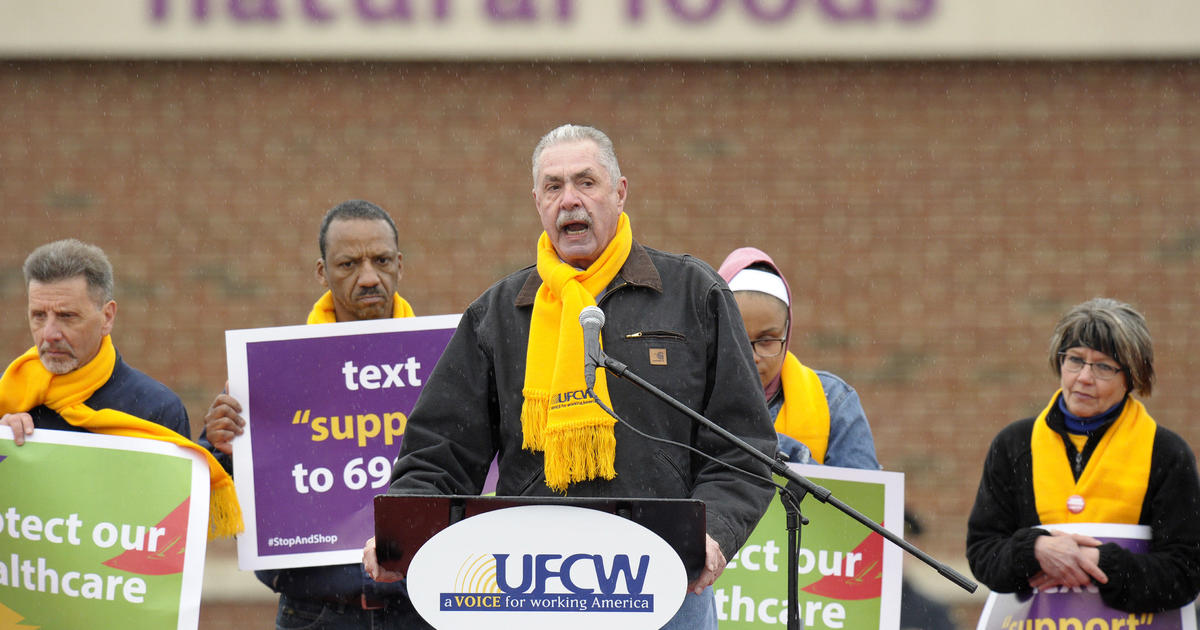

“Nobody thinks when they go to a food store that they may get something at work that may not allow them to live the rest of their life,” Perrone said. He spoke with CBS MoneyWatch about how the virus is affecting food and other essential workers. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How has the coronavirus changed the way people shop?

Marc Perrone: On a normal day, there may be anywhere from 1,500 to 2,000 people in a grocery store. During the early stages of the pandemic, there were as many as 10,000 people through those stores on a daily basis.

We’ve seen people get really, really upset — just because we’ve asked people wear masks inside stores. And they’ve gotten really upset when we were in those early stages that were asking people to limit their purchases to, say, one package of toilet paper or one can of Lysol spray. The customers were afraid, and they were in survival mode.

What should stores do about customers who don’t wear masks? Many have said they don’t want workers to be the “mask police” for customers.

I don’t think that our workers ought to be the mask police, either. The management in the store, quite honestly, they’re the ones that control the keys, they’re the ones that should say something to the consumer. And if they have a customer that’s being unruly, they always have the ability to call the police and ask the police to show up.

I can certainly tell you that from personal experience, if I was to go to a location and start to talk about unionization somewhere that happened to be non-union, believe me, they’ll call the police on me to get me out of there.

Some people say they can’t wear masks, or simply decline to do so as a matter of personal choice. What’s your response?

Look, 10 years ago I went through open heart surgery. And I have to wear a mask wherever I go, and I wear an N95. Is it hard to breathe with an N95? It is. But the way I look at it is that I’m trying to protect myself, and I’m also trying to protect the person that’s serving me. So I’m willing to do the little bit of discomfort.

Do I think they have a legitimate concern? Sure. But they could wear a face shield. There are other ways to try to slow or stop that spread of any aerosol particles coming out of your mouth. And if we want to open our economy, we need to figure out a way that we can open this economy safely for people so that they don’t have to run the risk.

I was on a call with one of my members out of Detroit, Michigan, and he was telling us that early in March, he caught COVID-19. He went into the hospital and he was in there for four weeks. He was on a respirator for three and a half weeks. They didn’t think he was going to live. He’s now out of the hospital, but he has to take blood thinners and also blood pressure medicine, because there is a really strong fear now that he’s going to have a stroke because of the impact that it had.

What responsibility does an employer bear if an employee contracts COVID-19 at work?

We can’t determine where we catch this virus, right? The only thing that we can do is provide enough protections to limit the possibility of them getting it while they’re at work. I don’t think that the employers have the responsibility — as it relates to somebody that may have passed away — unless they didn’t do anything to try to protect the workers. In other words, [if] they didn’t try to mandate the mask of the customers going into the stores, or they didn’t provide personal protection equipment.

One of our employers, midway through this pandemic, said they were going to stop supplying masks to their own employees. And so when when you’re talking about those sorts of conditions or those sorts of actions by an employer, should they be held responsible? I think they should be.

I think there needs to be more transparency around this whole conversation. What did you decide to do to protect [workers]? When did you protect them? What are you doing in order to further enhance that protection?

Should workers be able to sue their employers if they get the virus?

As long as an employer is, in fact, meeting the criteria that has been given out so far by the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] and trying to meet that criteria, then they should be exempt. I would submit to you that the court system is the last place that somebody can adjudicate this right. And if in fact, you can’t adjudicate it through the regulatory system of our government, because OSHA has not come out with any standards, then there’s no other place for the worker to go.

Shortly after the pandemic began spreading in the U.S., some employers started offering front-line workers “hazard pay” — typically a modest bump in hourly wages — to compensate them for the health risks. But most companies pulled the plug on that money even as the death toll mounts. What happened?

I think some of it had to do, initially, that unemployment levels were low. Stores were afraid they were going to lose their workers. So they came with the hazard pay, and they came with the PPE. But when the unemployment levels went to 45 million, it was a whole lot easier to find replacement workers, and they started dialing back the hazard pay, even though their sales were up. Even though the cost of groceries are going up and their profit margins are going up, even though productivity is going up — they decided to dial the hazard pay back, but the hazard’s not gone.

Here’s the deal — In business, if you’re going to invest in something, the more risk you take, the higher return you get. And a grocery store, if you’re going to go to work and you’re going to have more risk for you to be there at work — that you might not show up at home or you’re going to die — then you should get more pay for the work that you do.

Now, presently, most of the money, the excess profits, in most of the companies are being directed towards their shareholders. And I’d ask one question: What risk are they taking right now? Most of them are sitting at home behind the screen. It’s just … it’s not American, not fair.