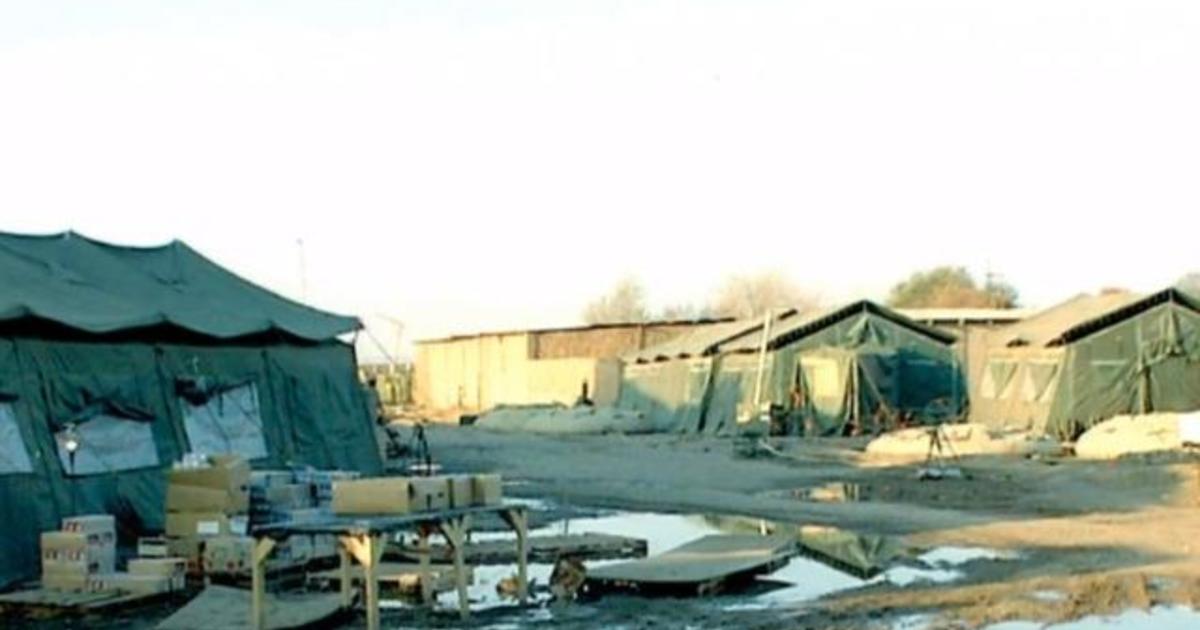

A CBS News investigation reveals new evidence in the cases of service members who believe their rare cancers and other illnesses stem from their time served on a remote base after 9/11. They say they were exposed to toxic materials at Karshi-Khanabad, or K2, a former Soviet base in Uzbekistan.

U.S. troops first deployed there 19 years ago.

“I had no idea at 40 that this would be my life,” former Air Force mechanic Doug Wilson told CBS News senior investigative correspondent Catherine Herridge.

Wilson said he can no longer work or drive after a rare cancer caused brain damage. Wilson, his wife, Crystal, and their two children rely on disability payments and Crystal’s teacher salary.

“I think the biggest thing that breaks my heart is just the confidence that he’s lost in himself,” Crystal said.

Doug is one of nearly 2,000 current and former service members who flooded a Facebook page, self-reporting cancer, neurological disorders and other illnesses. They believe it is linked to their military service at K2.

After 9/11, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs says about 10,000 troops passed through K2 over a four-year period, supporting missions hunting al Qaeda. But while stationed there, some say they were surrounded by dangerous, toxic waste at the running track and at a site nicknamed “Skittles Pond” for its changing shade.

Now, for the first time, a Department of Defense employee involved in testing at the base is going on the record.

“One hundred days, we thought we’d be out of there,” Mike Lechlitner, who was among the first to arrive at K2, told Herridge. “I served as part of a small team that provided support to our special operators going further downrange into Afghanistan.”

But just days into Lechlitner’s mission, he says local workers hired to build a dirt barrier started getting sick.

“They were fainting, getting dizzy and getting nauseous,” he said.

Soon after, Lechlitner was asked to help identify testing sites across the base.

“First test site we dug, a liquid substance seeped up, gold in color, and smelled like jet fuel, which made sense because … they had tanks of fuel there that had probably been leaking since the Soviet day,” he said.

He was also asked to gather intelligence on the base’s history.

“We learned that the Soviets had had a chemical weapons decontamination unit adjacent to our camp,” Lechlitner said.

Low-resolution satellite imagery shows the aftermath of a massive explosion in 1993 at the base’s weapons depot. Lechlitner said the explosion scattered toxic material including asbestos and a refined form of uranium ore called yellowcake.

The readings were “7 to 9 times higher than normal background radiation,” Lechlitner said.

“And they found a fragment that was handed to me bagged and was described as, this is a piece of yellowcake.”

“You’re saying that the explosion in 1993 pulverized yellowcake uranium and spread it across the base?” Herridge asked.

“It is my understanding based on the readings,” Lechlitner said.

A base surgeon was also concerned. He wrote an environmental exposure memo obtained by CBS News for his unit’s permanent medical record in case they got sick. It documents “arsenic and cyanide present in the soil, air and water.”

Doug and Crystal were stunned by what we learned.

“Disappointed is not even the right word,” Crystal said.

“That’s crazy that they would let us work in that kind of environment,” Doug said.

The VA “found no link between (Doug Wilson’s) diagnosed medical condition and military service.” Doug appealed the decision with a letter of support from his oncologist stating his cancer is “more than likely” connected to toxic exposure. A year later, the appeal is still pending.

Asked what difference it would make if the VA acknowledged his brain cancer is connected to his service, Doug said, “It would open up a flood of programs.”

Programs such as grants to make their home more wheelchair accessible and more money for their family’s future.

“Almost $2,000 more a month,” Crystal said.

That would make “a huge difference” for their family, Doug said.

Lechlitner only learned a few months ago that so many service members were suffering.

“They were the finest group of Americans I’ve ever served with and these were the people that were first in,” Lechlitner said.

In a statement, a VA spokesperson said disability claims are decided on a case-by-case basis and the VA is “closely following the possible health effects of K2 deployment.” In a preliminary review, the VA says it found the death rate for K2 veterans is lower than the general population, though a larger research project is ongoing. The Defense Department did not provide a statement.