U.S. authorities along the border with Mexico apprehended nearly 1,000 unaccompanied migrant children in the span of six days last week, as unauthorized crossings by minors continue to rise, according to government statistics provided to a federal court.

From November 18 to November 23, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) processed 997 migrant minors who traveled without parents or legal guardians, the agency’s top official, Mark Morgan, said in a court declaration Wednesday. More than 9,900 unaccompanied children have been taken into custody since September 8, Morgan added.

Within the next 120 days, CBP projects border crossings by unaccompanied minors to increase by 50%, according to the court declaration.

Morgan disclosed the figures as part of a Trump administration request for the D.C. Circuit Court to suspend a lower court order that currently prohibits border officials from expelling unaccompanied migrant children without a court hearing or an asylum screening. The outgoing Trump administration has argued that the policy, which it dubbed the “Title 42” process, is needed to prevent potentially infected migrants from spreading the coronavirus inside holding facilities and elsewhere in the U.S.

Last Wednesday, Judge Emmet Sullivan of the U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C. ruled that the public health law being cited by the Trump administration to expel border-crossers does not authorize expulsions or supersede legal safeguards for migrant minors — even during a pandemic. Sullivan ordered officials to stop expelling unaccompanied minors, but did not do the same for families with children or single adults, who continue to be expelled to Mexico or their home countries.

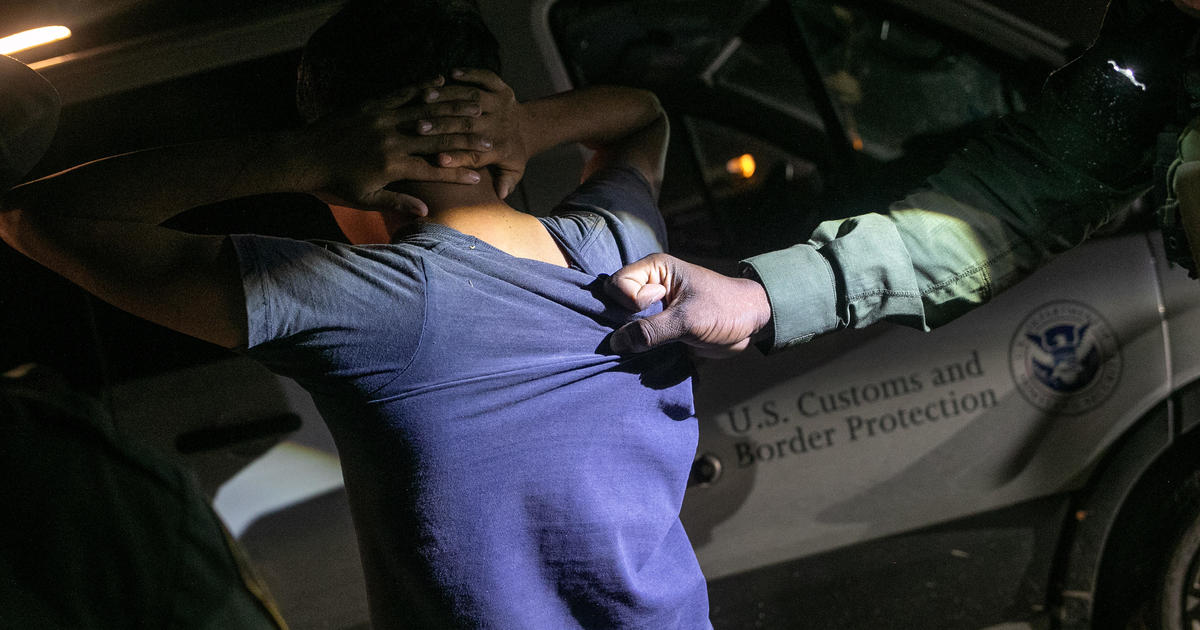

U.S. Border Patrol agents detain a 16-year-old undocumented immigrant minor from Mexico on September 10, 2019 in Mission, Texas.

/ Getty Images

In his declaration, Morgan said the uptick in apprehensions of unaccompanied minors is linked to last week’s court ruling, which he argued will “serve as a pull factor.”

Lee Gelernt, an American Civil Liberties Union attorney who has been challenging the border expulsions, pushed back on Morgan’s statements and predictions.

“The assertion that there will be a sharp increase in border crossings by children this winter is speculative at best, and in any event children can be safely tested and quarantined as needed,” Gelernt told CBS News. “There is simply no basis for the Trump administration’s claim that the cruel and patently unlawful Title 42 policy is necessary to protect public health.”

Apprehensions of unaccompanied migrant children along the U.S.-Mexico border, which plummeted to 741 in April, had been increasing steadily before Sullivan issued his order. In September and October, CBP agents apprehended 3,883 and 4,764 unaccompanied minors, respectively.

The U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement, where most unaccompanied migrant children were sent before the pandemic, is now housing more than 2,300 minors in its network of shelters, an increase from a decade-low early in the summer, when the in-custody population dropped below 800.

Migrant minors transferred to the refugee agency stay in shelters or other housing facilities until they are placed with a sponsor, who is typically a family member residing in the country. U.S. law allows them to request asylum or other forms of humanitarian refuge to stop their deportation proceedings.

After receiving 162 children between April and June, the Office of Refugee Resettlement received 1,218 and 1,530 migrant minors from border officials in September and October, respectively.

While the refugee office has space to house approximately 13,000 minors, less than 8,000 beds are available because of Covid-19 mitigation policies, Nicole Cubbage, the agency’s acting director, said in a declaration accompanying the Trump administration’s appeal of Sullivan’s ruling. Cubbage said her office expects shelters along the southern border to reach maximum capacity on December 12, and the entire nationwide bed space for migrant children to be depleted by early January.

If the trend holds, Cubbage said the refugee agency would need to reopen “influx facilities” in Homestead, Florida and Carrizo Springs, Texas, to house hundreds of migrant youth. Cubbage said her office could start receiving between 300 and 400 children daily in “the near future,” a prediction she attributed to Sullivan’s order, “deteriorating economic and political conditions” in Central America, the impact of recent hurricanes, seasonal patterns and even President Trump’s electoral defeat.

“I am concerned that the recent upward trend in referrals noted above could represent the cusp of a major influx of UAC,” Cubbage wrote, using an abbreviation for the government term, “unaccompanied alien children.”

Detention periods for migrant children are also increasing. In September and October, 71 minors spent more than three days in Border Patrol custody, according to government statistics provided to lawyers representing detained migrant children.

According to the data, a three-month-old apprehended with at least one parent was held by CBP for two weeks. In October, a 17-year-old unaccompanied teen was in CBP custody for 18 days. In court declarations filed earlier this week, several children interviewed by a lawyer alleged having limited access to soap and face masks, and denounced lax social distancing measures and crowded conditions in CBP facilities.

“My mask is dirty on the inside. Here, people do not practice social distancing,” an eight-year-old child said, according to one of the declarations.

Another minor, a 15-year-old from El Salvador, said: “I was detained in a room with thirty other minors and we were cramped. I felt uncomfortable because there were so many people in the room. I had to sleep in a sitting position because there were so many people in the room.”

CBP did not address these allegations, citing pending litigation.

A 2008 anti-trafficking law requires CBP and other agencies to transfer unaccompanied minors to the refugee office within 72 hours of apprehending them, absent extraordinary circumstances. “Failing to lawfully transfer these children in time is simply negligent,” Democratic lawmakers led by Hispanic Caucus chairman Joaquin Castro wrote in a letter this week to acting Department of Homeland Security secretary Chad Wolf.

Neha Desai, one of the lawyers representing migrant youth in the court case over the Flores Settlement Agreement, which governs the care of minors in U.S. immigration custody, said the government needs to take more steps to quickly transfer children out of CBP custody. “Having children detained in CBP custody for any amount of time exposes them to a dangerous and traumatic environment,” Desai told CBS News. “This was true well before the pandemic and is even more so the case now.”

Border Patrol agent Justin Castrejon looks out along newly replaced border wall sections Thursday, Sept. 24, 2020, near Tecate, Calif.

Gregory Bull / AP

On Wednesday, CBP announced it would be closing its largest temporary detention facility for migrant families and children until renovations are completed in early 2022. The Central Processing Center in south Texas, opened during the Obama presidency, became notorious for its chain-link sections, which were denounced by advocates as “cages” when the Trump administration systematically separated thousands of migrant families in 2018. The announcement was first reported by The Washington Post.

The increase of border crossings by children, and of overall apprehensions, could prove to be an early and thorny immigration policy test for the incoming Biden administration. President-elect Joe Biden has vowed to discontinue many of Mr. Trump’s border programs, including a policy that has required tens of thousands of asylum-seekers from Central America, Cuba and other Latin American countries to wait in Mexico for their U.S. court hearings.

Mr. Biden’s team has also pledged to review the expulsions policy to ensure border-crossers “have the ability to submit their asylum claims.”

Andrew Selee, president of the non-partisan Migration Policy Institute, said ending the “Remain in Mexico” program and the expulsions too quickly could lead to a surge in border crossings. He suggested the incoming Biden administration could end Remain-in-Mexico but temporarily retain the expulsion policy, a scenario that could be complicated by legal challenges and reporting that shows public health officials were pressured by the White House to authorize the expulsions.

Selee said an influx in border arrests could hurt chances of a divided Congress passing immigration legislation, including one that provides a pathway to U.S. citizenship for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) beneficiaries. Republicans lawmakers blamed the DACA program for a surge in border apprehensions of Central American children in 2014, even though the policy, established in 2012, did not benefit new arrivals.

Before completely ending Mr. Trump’s policies, Selee said the incoming Biden administration should deploy more asylum officers, surge resources to the border and expand case management programs that allow migrants to complete their U.S. immigration proceedings outside of detention centers. Otherwise, he added, a sharp increase in unauthorized migration could leave the U.S. government unprepared, worsen conditions in temporary migrant holding facilities and lead to more draconian enforcement policies.

“You’re stuck between a rock and a hard place: Either you start releasing people in the general population or you hold them in the middle of a pandemic,” Selee said.

“If you try to be the anti-Trump on day one, you will end up acting like Trump in the end,” he added. “If you try and throw out everything Trump has done on day one, without having an alternative in place, you’ll end up doing the same things Trump did.”