Writer and teacher Colman McCarthy begins each school year with a pop quiz – and a cash prize. “I pull out a hundred dollars: ‘If anybody can answer the quiz, all names, it’s yours,'” he said.

McCarthy asked correspondent Mo Rocca to take the quiz.

“Who is Robert E. Lee?”

“He was the general of the Confederate Army, of Northern Virginia,” said Rocca, starting off confidently.

“Who was Napoleon?”

“He was a guy with a complex?”

“Yes, yes. The French general. Good! It’s looking good. It’s looking good,” said McCarthy. But then …

“Emily Balch?”

“She’s not the woman who wouldn’t go out of her house in Massachusetts, and wrote poetry?” asked Rocca, hesitatingly.

McCarthy explained, “No. Emily Balch was a Nobel Peace Prize-winner that founded the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.”

Nor could Rocca identify Jody Williams (a Nobel-winner for her work with landmines), or Jeannette Rankin (the first woman elected to Congress, and the only member to vote against American involvement in both world wars).

“Mo, don’t feel bad,” McCarthy said. “It’s always safe money. I can always count on American education!”

For 38 years Colman McCarthy has been trying to give away that hundred dollars to the more than 30,000 high school and college students in the Washington D.C. area who have taken his course in peace studies. A former columnist for the Washington Post, McCarthy has spent his life preaching, and teaching, non-violence.

“There are options to deal with conflicts in other ways,” he said. “But we don’t teach them the other ways, so they look on people like me: ‘Well, you’re one of those old ’60s hippies, one of those old liberals, still hangin’ around, aren’t you?'”

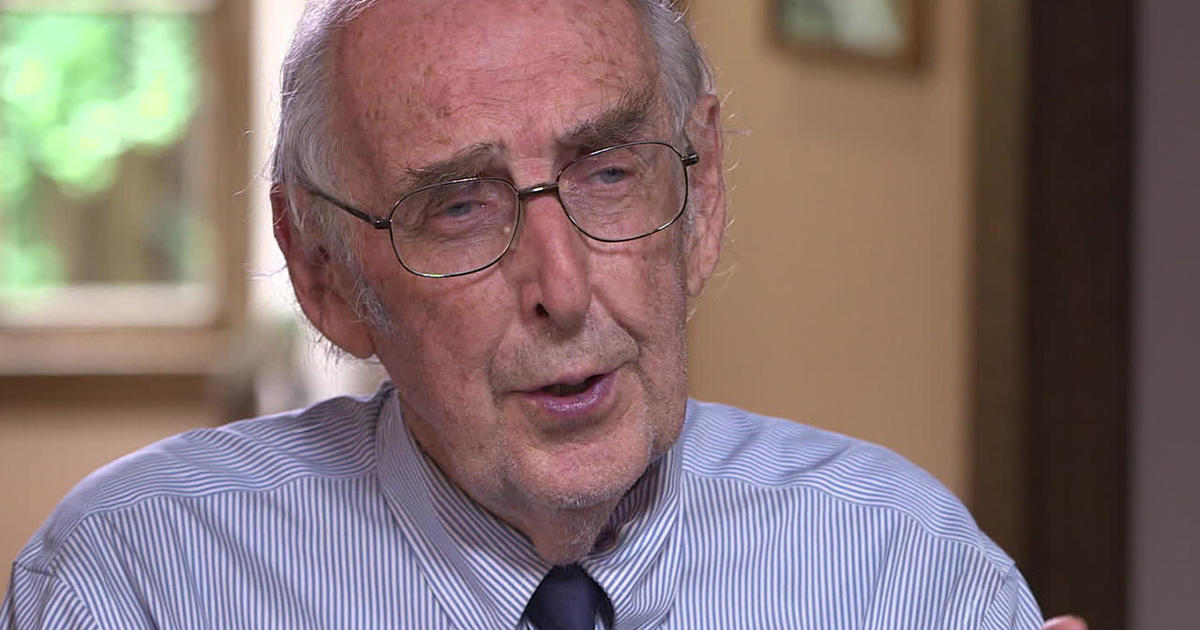

Peace studies teacher Colman McCarthy.

CBS News

McCarthy’s own journey began 82 years ago when he was born to an immigrant Irish family on New York’s Long Island. He went to Spring Hill College in Alabama, where he pursued his first passion: “I went there for 18 reasons, Mo. It had a golf course on the campus.”

He turned pro his senior year. But he’d also discovered the writings of Trappist monk and social activist Thomas Merton, and driving back home from Alabama, he stopped at a monastery in Georgia. He ended up staying five-and-a-half years

Rocca asked, “How come you didn’t become a priest?”

“I didn’t like the taste of wine,” McCarthy laughed.

His calling, it turned out, was journalism. In 1969 he began writing for the Washington Post, where he interviewed and befriended many of the 20th century’s most prominent peace advocates.

He told an audience, “I get a fair amount of mail from every week from readers around the country, calling me a fool, a jerk, a know-nothing … and then I read my negative mail.”

But don’t let his jovial manner fool you. McCarthy is nothing short of radical in his opposition to the violence he sees all around us.

He doesn’t believe we should have a standing army. Rocca asked, “Do you think we should have border security?”

“I don’t believe in borders,” he said. “Borders are artificially created, mostly by military action.”

He has no use for the national anthem. “I’ve never stood up for ‘The Star-Spangled Banner,’ because that is a war song. It’s about bombing people, it’s about rockets, it’s about a useless war.”

He’s against both the death penalty and abortion. “But I don’t criticize anybody who’s had abortions. I don’t want the government involved. But I do think we ought to educate everybody that there are other means to solve an unwanted pregnancy.”

If you think you know how McCarthy votes, well, he’s never voted. His commitment to non-violence extends beyond humankind, which is why he hasn’t eaten meat in decades.

Rocca asked, “Is anything you’re wearing from an animal?”

“No, my shoes are not leather. But good try!”

He doesn’t own a car; instead he bikes to work. “I do have a little dark side to me, Mo, about my bicycle, I love it when there are traffic jams. There they are, just polluting the atmosphere. And I breeze right on through. And for a couple of seconds I feel so morally superior!”

He brings about 20 speakers a semester to his class at Bethesda-Chevy Chase High School in Maryland, where he teaches on a volunteer basis. That’s right: McCarthy doesn’t get paid to teach here. Guest speakers have included Nobel laureates Mairead Corrigan, Muhammad Yunus, and Adolfo Pérez Esquivel.

And then, he brought in a maintenance worker from the school, a cleaning lady who’d fled El Salvador when she was 14, and never went past sixth grade.

Teacher, journalist and peace advocate Colman McCarthy.

CBS News

Gabrielle Meisel, Kyle Ramos and Caroline Villacis were all students when Rocca dropped in on McCarthy’s class before the pandemic. He asked, “How is your life gonna be different after you leave here for having taken this course?”

“Originally I was thinking of maybe going into a creative field,” Villacis said. “But now I’m looking for something more, I guess, practical, where I’m actually hands-on helping people. So, I’m thinking of being a social worker.”

Ramos said, “For me, it’s kind of just installed a sense of responsibility that I kind of need to, like, help other people and just help our world we’re in.”

McCarthy also “just brings out the best in people,” said Meisel. “He sees the strength in us. And he makes sure that every student knows how important they are, which is really awesome.”

McCarthy’s class has no exams and no grades. “He considers grades academic violence,” said Villacis.

Rocca asked, “Would you agree?”

“I would agree!” she laughed.

Rocca asked McCarthy, “Peace education, is that your calling in life?”

“Well, my calling in life is to be a good husband and a loving father and a loving husband. I think that comes first.”

He’s been married to his wife, Mav, for 54 years. The couple has three sons.

“It’s one of the dark secrets about the peace movement – so many of the great peacemakers were wretched people at home,’ McCarthy said. “They were cruel in ways we rarely hear about. Gandhi was an awful husband and father, a very domineering husband.”

“Peace begins at home?” asked Rocca.

“Yes, exactly.”

While Colman McCarthy’s class has no exams or grades, he does send his students home with one important assignment: “Every class, I say, ‘Your homework is to tell someone you love them today. And if you can’t find someone to tell ’em that you love them, look a little harder. And if you still can’t find ’em, call me up. I know where all the unloved people are. They’re everywhere.'”

For more info:

Story produced by Amol Mhatre. Editor: Emanuele Secci.