Over the years we’ve done a number of stories about wrongly convicted prisoners who get exonerated when a crusading attorney takes on their case. In prisons around the world, however, that rarely happens. In Kenya, for example, more than 80% of inmates have never been represented by a lawyer. Justice Defenders would like to change that. It’s an organization started in Africa by a soft-spoken, 37-year-old lawyer named Alexander McLean. Justice Defenders has worked in 55 prisons in Kenya, Uganda and The Gambia giving legal training to hundreds of inmates who can then help their fellow prisoners, the innocent and the guilty, get a fair hearing in court. They are also helping some prisoners get law degrees, and as we found out when we visited Kenya before the pandemic, the results have been astounding.

How COVID-19 transformed the Kenyan court system

Thika Main Prison outside Nairobi is a miserable place. Built almost seventy years ago to hold 300 prisoners – when we visited three years ago, there were more than 1000.

In this one dank holding cell, 140 men were packed tightly together. The air thick with the smell of sweat, and urine. They’d been accused of everything from trespassing, and robbery, to assault and murder. Some have already been convicted but most have yet to stand trial. They can’t afford bail, so they’ll likely have to wait here for years.

Alexander McLean

Alexander McLean: Good afternoon brothers. Our work is to help people who don’t have lawyers to access justice.

That’s Alexander McLean, the founder of Justice Defenders, which has been working in Kenya’s prisons for 13 years.

Alexander McLean: How many of you have a lawyer?

Just three men in this group of more than 200 prisoners have an attorney. Defending the defenseless is at the heart of Alexander McLean’s mission.

Anderson Cooper: Most of the people who are in prisons in Kenya don’t come to court knowing their rights knowing– how a court works.

Alexander McLean: You might meet people in prison– who think that the police are the ones who’ve convicted them of an offense. Or they’ve never had a copy of their judgment. So they know that they’ve been convicted, but they don’t know exactly what of– and why.

Alexander McLean: And so our hope with our work is that we give people fair hearings– So even if they’re convicted or they’re given a prison sentence, afterwards they say, “Well, that’s fair– because– my voice has been heard.”

Morris Kaberia was sent to Thika prison in 2005. He was a police officer and was accused of stealing a cell phone and credit card.

Anderson Cooper: How much time do you end up– in pre-trial detention, waiting for your trial?

Morris Kaberia: Eight good years.

Anderson Cooper: Eight years?

Morris Kaberia: Eight years. From 2005 to 2013.

In court, he claimed he’d been framed because he didn’t pay a bribe to a superior officer. The judge found him guilty of armed robbery and gave him the mandatory sentence: death.

Anderson Cooper: The death penalty for an armed robbery?

Morris Kaberia: Yes.

Anderson Cooper: When the verdict came, do you remember that day?

Morris Kaberia: Very much. When the judge sentenced me to death– to suffer death by hanging, I just saw black, darkness everywhere.

Morris Kaberia

McLean took us to Langata Women’s Prison in Nairobi, where Justice Defenders has trained 47 inmates to be what they call paralegals. They’re given a three-week law course, which enables them to teach other prisoners about bail, court procedures, and rules of evidence. The paralegals also prepare petitions and write appeals challenging inmates’ convictions and sentences.

Anderson Cooper: What year did you arrive here?

Jane Manyonge became a paralegal five years ago. She was a schoolteacher when she was charged with killing her husband, who she says was abusive. Convicted of murder, she too was given a mandatory death sentence.

Anderson Cooper: You didn’t know your rights, you didn’t–

Jane Manyonge: Never, never.

Anderson Cooper: How courts work–

Jane Manyonge: And that’s what propelled me to join the paralegals. That legal, basic knowledge that I get, it goes a long way. You don’t need a degree to draft somebody an appeal, or something like that.

Anderson Cooper: How does that feel?

Jane Manyonge: You feel that you are still a human being, even if you are here. You can do something to change someone’s life.

Alexander McLean began volunteering to help others as a teenager growing up in South London. His father was Jamaican and his mother is English. He first went to Africa when he was 18 to do hospice work in prisons and hospitals in Uganda.

Jane Manyonge

Alexander McLean: We went onto this ward, and by the toilet on the floor I saw a man– lying on a plastic sheet in a pool of urine. And for five days– I washed him and tried to advocate for him. Came the sixth day and he was lying dead and naked on the floor

Anderson Cooper: It’s not something a lot of people I think would volunteer to do.

Alexander McLean: I guess that sometimes in life, we see things that we can’t unsee, and then we have a choice as to how we respond to them.

Alexander McLean: Because every person has gifts, and talents, and something to contribute to our society. Our society can only flourish when– the inherent worth of each person is valued.

After returning to London, and graduating from law school, he could have gotten a high paying job. Instead, in 2007, he started a charity to improve conditions in African prisons. At Nairobi’s Kamiti Maximum Security prison, a notorious and sometimes violent place, he met George Karaba who was on death row for killing a man in a dispute over land.

George Karaba: I remember the first thing that we asked was how he could be able to provide us with reading materials.

So McLean began collecting whatever books he could find for the prisoners.

Alexander McLean: My sense was that books could transform us and– and transform our circumstances and take us– to a different place.

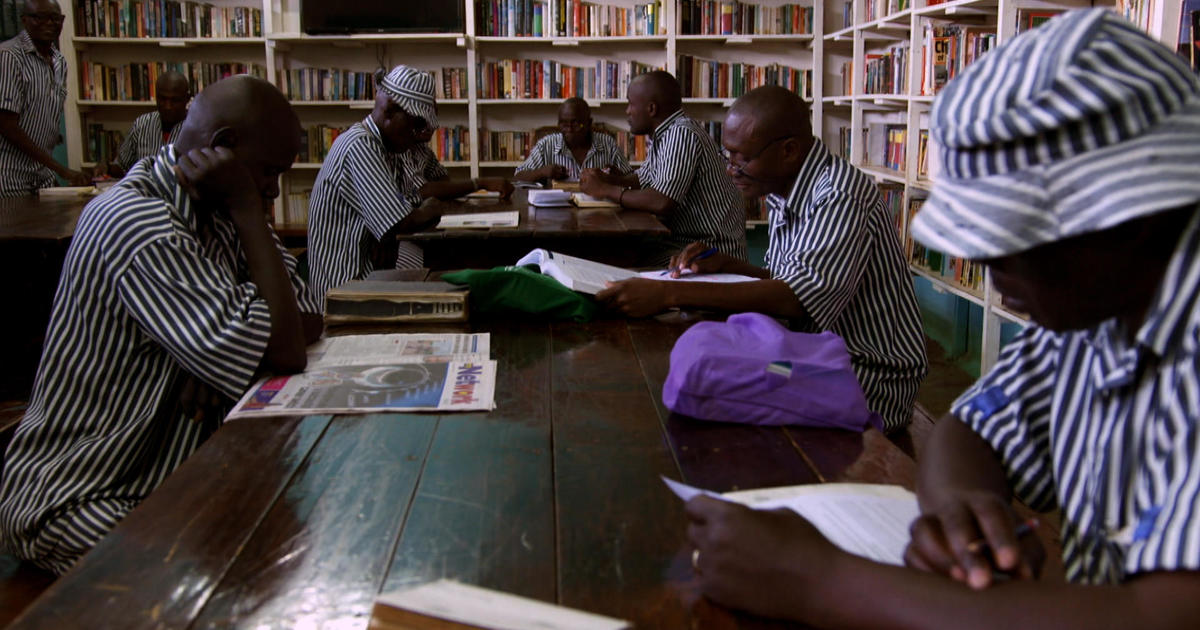

Prison authorities had already started an academy of their own, with classes from first grade through high school teaching math, English, science, and religion and with McLean’s help they turned a room at the end of a cell block into a library.

George Karaba: You can’t imagine the happiness. You can’t imagine–

Anderson Cooper: Just from a book.

George Karaba: Yeah. Because when I start reading this book, and it’s actually enlightening me. It’s like now, I’m being opened up to the outside world. It started giving us hope.

George Karaba

McLean wanted to do more than just improve life in Kenya’s prisons, he wanted to make sure those accused of crimes had a fair hearing.

Alexander McLean: Often there’s people from backgrounds of privilege who become lawyers, or become politicians and make the law, but it’s the poorest people in our societies who disproportionately feel the impact of the law. And I wondered what it’d look like to tap into that lived– experience.

So in 2012 McLean arranged with the University of London Law School for inmates to begin taking a three-year correspondence course, the same one Nelson Mandela took when he was in prison. To qualify, they have to pass an entrance exam and have a track record of helping other prisoners while they’ve been behind bars.

Anderson Cooper: So even if they may have murdered somebody and have– a life sentence– if– if they have transformed themselves in prison, if they are serving others, they might be able to qualify?

Alexander McLean: Yes. Because we believe that there’s more to someone– that’s killed than being a murderer or more to someone that’s– who’s stolen than being a thief. I don’t think any of us has to be defined by the worst thing that we’ve done.

Remember Morris Kaberia, the cop in for armed robbery? He enrolled in law school and found the learning curve steep.

Morris Kaberia: I had never touched a computer in my life before I went to prison.

Anderson Cooper: Really?

Morris Kaberia: Yes. I touched the first– computer in that law class.

The mock legal hearing at Kamiti Maximum Security Prison

In some ways, they are like law students anywhere. In the chapel at Kamiti Maximum Security Prison, we watched as they held a moot court, a mock legal hearing where they role-play, arguing cases with all the gravitas and grandeur of a real Kenyan courtroom.

Some prisoners play prosecutors. Others, the defense. There’s also a defendant. And prisoner judges to render a verdict.

You may have noticed prison guards in attendance, remarkably some of them are taking law classes as well. Willie Ojulu, is the chief inspector at Langata Women’s Prison, and just completed his University of London law degree.

Anderson Cooper: I don’t know that I know of many guards in the United States who train to become a lawyer so they can give legal advice to the people they’re guarding. It’s pretty unique.

Willie Ojulu: Well, it sounds unique, but that’s what happens here. You know, people are brought to prison as a punishment, but not for punishment.

Anderson Cooper: I’ve never heard it phrased that way. So your goal is not to punish them? But…

Willie Ojulu: But to help them improve on their life and manage their life properly, so that they don’t get in conflict with the law.

Willie Ojulu

Three years ago inside Kamiti Maximum Security Prison, there was a graduation ceremony the likes of which no one here had ever seen. Eighteen inmates – former prisoners and guards – received their University of London law school degrees. George Karaba got his, and while he may spend the rest of his life in prison, he says he’s been transformed.

George Karaba: Even if I do not get out of prison, I will still continue doing what I do.

Anderson Cooper: To see somebody you’ve helped get out of prison–

George Karaba: It gives me great satisfaction.

Anderson Cooper: Does it feel like part of you goes out with that person?

George Karaba: Yeah. I feel part of me is actually out. And therefore, I’m good.

George Karaba and others helped Morris Kaberia appeal his death penalty convicition. Kaberia argued the case himself and was stunned when the judge acquitted him of all charges after 13 years in prison.

Morris Kaberia: I felt like– I– I– I did not hear right. So I asked her, “What?” (LAUGH) And she told me, “Hey, come on. I thought you’re a lawyer.”

Anderson Cooper: You didn’t believe what she was saying?

Morris Kaberia: I– I don’t believe–

Anderson Cooper: You wanted to see it in writing?

Morris Kaberia: I don’t believe it can happen that way because I– it– it was not– even in my mind.

Morris Kaberia was freed, but when he got out, he went right back to prison as a full-time employee of Justice Defenders.

Morris Kaberia speaks to a class for Justice Defenders

Here he is teaching inmates a lesson he learned in court first hand: always look the judge straight in the eye.

Morris Kaberia: Don’t just lie low, don’t keep quiet, it might affect your defense or your case.

Justice Defenders says since we visited Kenya, they’ve provided more than 37,000 legal services to prisoners and seen almost 11,000 people released. This was Pauline Njeri’s walk to freedom, after five years in prison for fraud. Her daughter was there to greet her.

Pauline Njeri hugs her daughter after five years in prison.

This was Pauline Njeri’s walk to freedom, after five years in prison for fraud. Her daughter was there to greet her.

Anderson Cooper: Some of the people that your paralegals are training– have committed very serious offenses.

Alexander McLean: For sure.

Anderson Cooper: Do they really deserve, a chance to get out if– if they’ve really committed those crimes?

Alexander McLean: We’re not determining sentence.

Alexander McLean: Those who are guilty– of offenses should be punished. And the punishment should be– proportionate and it should be viewed towards equipping them– one day to leave prison and to contribute to society. But those who are innocent shouldn’t be– wrongly punished.

Justice Defenders relies entirely on donations, and spends about two million dollars a year helping inmates. They’ve begun trying to expand their work into other prisons in Africa, Europe, and the United States.

Already, their impact in Kenya has been profound. Morris Kaberia was part of a team of Justice Defenders who successfully challenged the constitutionality of Kenya’s mandatory death sentence. The law was changed, and as a result thousands of death row inmates became eligible for re-sentencing.

Anderson Cooper: That must feel extraordinary.

Morris Kaberia: Extraordinary. I love law. I love law. I eat law and drink law. I love law. I– (LAUGH)

Anderson Cooper: You eat and drink it–

Morris Kaberia: I sleep law. I–everythi– I do everything in law. (LAUGH)

Anderson Cooper: Listening to you talk about the law, it sort of makes me excited about the law.

Morris Kaberia: Yes. Let me tell you, Cooper. You know, there is one thing we do. We make assumptions as people, as a society. And we– dig our graves through those assumptions. Law is not for lawyers. Law is not for the government. Law is not for some people somewhere or the rich. Law is for everyone.

In the coming weeks 100,000 inmates will have been advised by Justice Defenders. With their planned expansion into new prisons and countries they aim to serve one million prisoners by 2030.

Produced by Michael H. Gavshon and Kate Morris. Broadcast associate, Annabelle Hanflig. Edited by Stephanie Palewski Brumbach.