Personal trainer and Cameroonian immigrant Simone Tchouke knows the importance of working hard. She used to train up to eight clients a day, until COVID-19 hit.

“It was really it was really bad,” Tchouke said. “We just kind of scaled down to, like, nothing. So enough to, like, pay your rent and pay food and that’s it.”

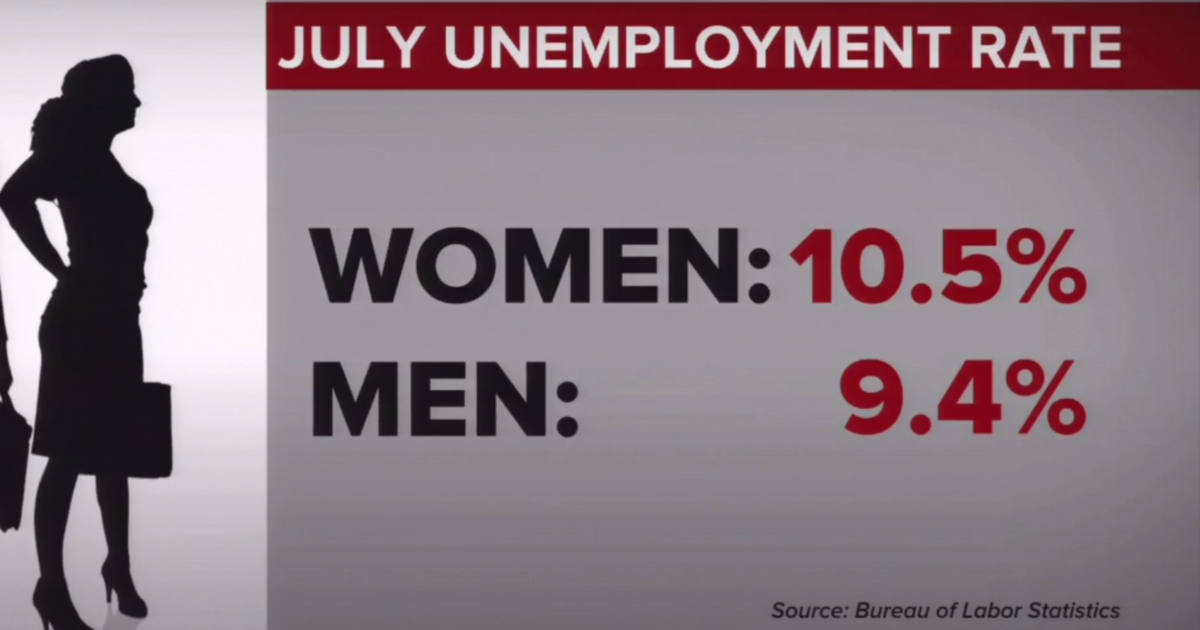

During the economic downturn brought on by the pandemic, women have suffered more job losses than men. In July, the unemployment rate for women was 10.5% while the rate for men was 9.4%. Women still in the workforce continue to face a grim reality — they make less than men. In 2018, the median earnings for women was $45,097 while men made $55,291.

Tchoucke says she isn’t able to charge as much as male trainers with the same amount of experience she has.

“It’s always so weird. Like, I don’t know why, but as a woman it’s always so hard to kind of impose my price,” she said.

In 2018, women earned just 82 cents for every $1 earned by men. The picture is even more stark for women of color: Black women earned just 62 cents for each $1 earned by men, and Latina women only earned 54 cents.

This is a driver of the cumulative lifetime earnings gap between men and women at retirement age, which is $1,055,000 according to Merrill and Age Wave.

“I think it has to do with a lot of antiquated…gender norms and rules and expectations that we have around who should be … the primary breadwinner,” said C. Nicole Mason, president and CEO of the Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

Personal Trainer and Cameroonian immigrant Simone Tchouke knows the importance of working hard

CBS News

She said COVID-19 has hit women particularly hard because women work predominantly in the service, education and health services sectors, which were the most impacted by the pandemic.

“When you couple that with the pay gap and the, you know, lack of savings, an economic shock, like the pandemic really hurts and cripples working women, especially lower-wage women,” she said.

Mason said shutdowns across the country put mothers still in the workforce at a disadvantage.

“There’s no school, there’s no daycare and women are expected to…work 40 hours a week and still be the primary caregiver. And it’s just an impossible situation for most women, especially women who don’t have the option of working remotely or home,” she explained.

Haycha Gonzalez, a mom of two from Connecticut, is one of those women. She said deciding what to do in the fall was a struggle. Ultimately, she will likely leave her job as a para-educator to homeschool her two children.

Para-educator Haycha Gonzalez will likely leave her job to stay home and homeschool her two children.

CBS News

“That’s definitely going to…leave a gap in my resume,” she said. The lack of income means “financial goals [have] to take a step back for a while.”

The pay gap persists because gender-based pay discrimination, although illegal, is widespread. Women also work in lower-paying jobs and might not have access to paid family leave or affordable childcare.

“If we do nothing, it won’t close for another 40 years,” said Mason. “For Black and Latina women, it won’t close for more than 100 years. So a century. So essentially, my daughter or my daughter’s daughter won’t see pay equity in their lifetime.”

Mason said the pandemic offers a unique opportunity to have a conversation about the pay gap, wealth building and a more equitable economy.

“[It] has really provided us an opportunity to think about women workers,” Mason said.

Simone Tchouke, who plans to go virtual with her business, is seizing her opportunity.

“Hopefully things get better,” she said. “So my goal is to create videos online on my website where people can subscribe and have access to my workouts.”

Like so many others, she is trying to salvage her business. Still, she plans to move out of New York City because she can no longer afford it.

“I just want to work,” Tchouke said. “When I say I need assistance, I don’t need somebody to give me money. I just need to work.”