Washington — As school districts decide whether to reopen classrooms for in-person instruction or begin with virtual learning for the upcoming school year, Connecticut Governor Ned Lamont said he fears waiting until there is a coronavirus vaccine to open up schools could lead to a “lost year of education.”

“I do not want a lost year,” Lamont, a Democrat, said in an interview with “Face the Nation” on Sunday. “When everybody says, ‘Let’s not go back to school until it’s perfectly safe, until we have a vaccine, until 100% percent of the people are vaccinated,’ I worry that could be a lost year of education.”

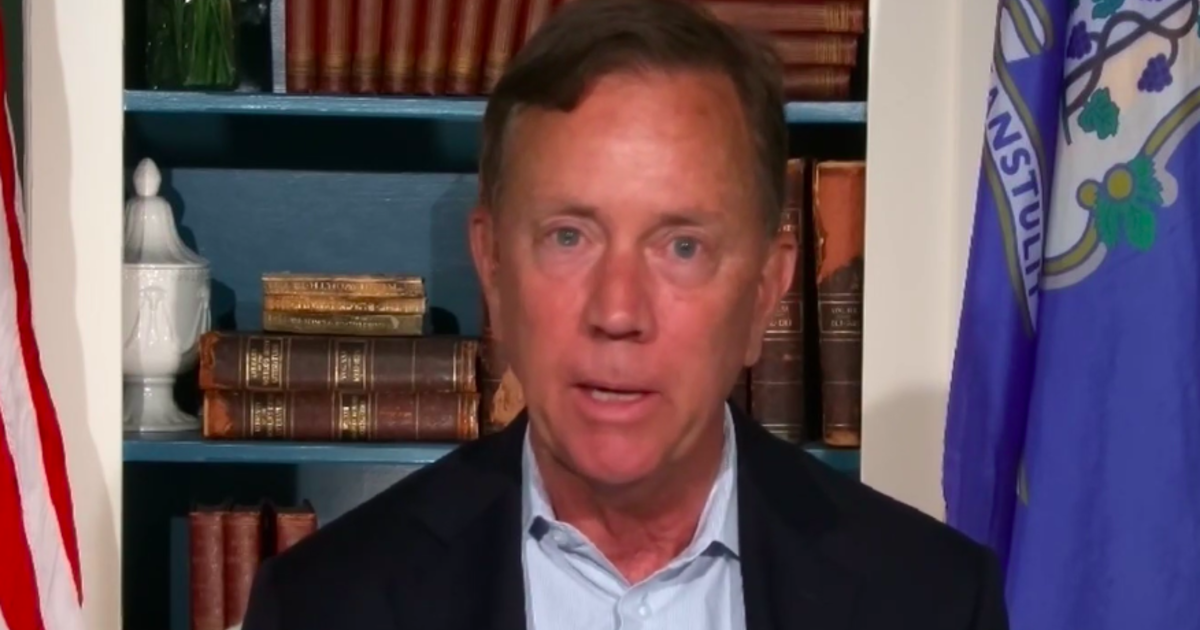

Transcript: Governor Ned Lamont on “Face the Nation”

Schools across the country closed their doors in March as the coronavirus began rapidly spreading across the U.S., switching to virtual learning for the remainder of the school year. Now, with students already returning to schools in some states, many districts are adopting hybrid models of learning or have opted to begin the first few months of the academic year online.

Lamont in June unveiled a framework for all Connecticut students to have the ability to access in-school, full-time instruction for the upcoming year and announced last week that the state would provide an additional $160 million to help school districts open safely. Still, one of Connecticut’s largest school districts, New Haven Public Schools, will petition the state to begin fully online.

After Lamont closed public school doors for classroom instruction in mid-March and eventually extended the closures for the rest of the school year, the state found 143,000 students didn’t log on for remote learning.

“It’s a tragedy,” he said of the children who failed to sign on. “We made it available to everybody we could, but again, requires parental supervision, requires a lot of effort to make sure everybody logs in. Right now, we’re going to have a telephone back up, better coordination, I think, with parents. But it’s by no means perfect.”

Lamont said heading into the next academic year, the state needs a backup plan in the event all districts have to return to online learning.

“We’ve bought 100,000 Chromebooks. We’re getting them installed in every kid’s home that doesn’t feel comfortable getting back to school,” he said. “The teachers’ homes, if they don’t feel comfortable getting back, expanded Wi-Fi so those kids can connect at least with their classmates over Zoom.”

In addition to weighing how to approach the new school year, states and cities are also grappling with the economic fallout from the coronavirus pandemic, as they have seen revenue streams dry up. Millions of Americans also remain out of work, and while the unemployment rate has fallen from 11.1% to 10.2%, the latest jobless rate exceeds the highest rate during the Great Recession in 2008 and 2009.

Congress and the White House spent the last few weeks discussing a legislative package designed to provide assistance for out-of-work Americans after the enhanced unemployment benefits expired at the end of July, but were unable to reach a deal.

The impasse prompted President Trump to act unilaterally through executive action that seeks to address evictions, student loan relief and unemployment benefits. One of his memoranda aims to provide $400 per week in unemployment aid, with $100 of it coming from the states.

Lamont estimated the arrangement detailed in Mr. Trump’s order, which he announced Saturday, would cost his state $500 million.

“I could take that money from testing. I don’t think that’s a great idea. I could take that money from, you know, mass disinfecting for our schools. I don’t think that’s a great idea,” he said. “In fact, I think the president’s plan is not a great idea.”