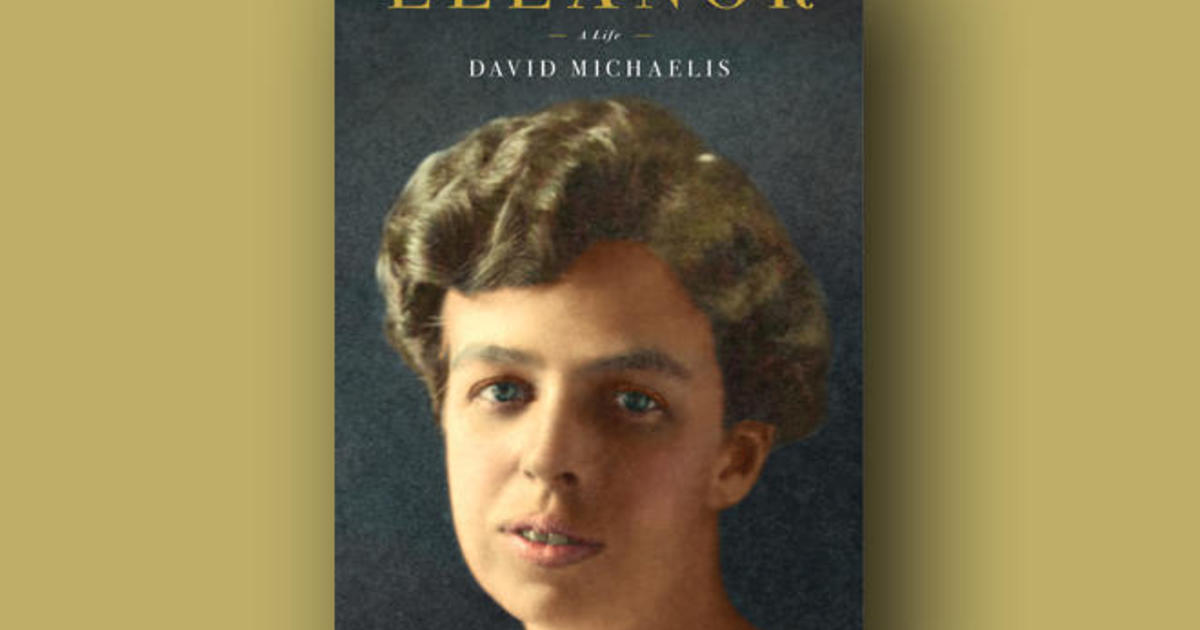

The new biography “Eleanor” (published by Simon & Schuster, a division of ViacomCBS) by David Michaelis, biographer of artist N.C. Wyeth and Peanuts cartoonist Charles Schulz, offers a surprising portrait of a first lady who became one of the most revered women in the world.

In this excerpt below, Eleanor Roosevelt, a woman born of privilege, captivates a public beyond the media image of her, an image that perhaps failed to appreciate fully her gifts as a communicator in an era of social upheaval, and an activist for the dispossessed.

Don’t miss Mo Rocca’s interview with David Michaelis on “CBS Sunday Morning” November 1!

Simon & Schuster

A car with Illinois license plates passed her twice, followed her into a gas station, then pulled up alongside and parked.

Happily, two young couples tumbled out to shake her hand. Said one of the women, “You look much nicer than your pictures.”

This had been happening since 1933. In Abingdon, Virginia – the town of her father’s painful exile – throngs of well-wishers had lined the streets, overhung with flags, and a band was leading Mrs. Roosevelt’s open-car processional up the packed main street on its way to the Mountain Music Festival, when the astonished voice of a little girl piped up: “Why, she ain’t so bad lookin’!”

Eleanor laughed and didn’t think about it again, until the same startled recognition began to repeat in other places, as people meeting her found themselves astonished that the Eleanor before them was far more lovely than the homely Mrs. Roosevelt of pictures.

“Your pictures libel you, Mrs. Roosevelt!” they called out to her. As she drove or walked on, thrilled whispers followed the encounter.

“I never realized Eleanor Roosevelt was so beautiful.”

“Even if her teeth were not right and the set of her face a little off,” one woman told her diary, “there was an extraordinary radiant quality about her.”

“You never told me she has such blue eyes,” took up the husband of a reporter.

One columnist gushed about her limbs: “I feel that I just have to say this, especially as I don’t think I have ever read it anywhere before. Honestly, Mrs. Roosevelt has beautiful legs and quite trim ankles and small slender feet!” Another noticed that for so tall a woman, “she has a peculiar undulating walk.” Still others were amazed by the elegance of her wardrobe and the fluidity that rolled through all her movements, all angularity of her long arms and legs “erased by the soft, flowing lines of her clothes and the relaxed manner in which she moves.”

Her height increased in the enchantment, gaining at least an inch in the telling, then another in diaries, and still another in the vast literature of the Roosevelt years. In real life she was an inch under six feet. Ernest Hemingway, a solid six himself, and no fan of adverbs, proclaimed Eleanor “enormously” tall. Esther “Eppie” Lederer, the advice columnist Ann Landers, was amazed when she met Eleanor: “I mean, she’s huge.”

Foreign visitors in the late-1930s were astounded to open a magazine or attend a Broadway musical and find the first lady of the land portrayed in so casual a manner. Her New Deal travels in the first administration so rapidly and completely transformed people’s image of her that by 1936, a common mystery probed in stories about Eleanor was how her “real” beauty had made people “forget her ugliness.” Some saw her gift of engaging with people’s hopes and dreams as an expanding expression of her Christian faith. Others argued that she hadn’t been ugly in the first place – only an “ugly duckling” beside her beautiful, swanlike husband. “Her ugliness may have been an asset,” diarized one young actress: “The vain silly side that is so noticeable in all of us pretty women is completely absent in her.” Life itself had “given her a richness that makes one forget her ugliness,” concluded her protégée Rosamond Pinchot. The writer Brendan Gill countered that it wasn’t a matter of having to forget: “the ugliness simply wasn’t there.”

New confidence in her own powers was the most common explanation. “She exuded strength, drive, curiosity,” commented one reporter, “and combined them with the ability to decide and to act. She had an exuberant belief that progress was there to be achieved, if only one worked hard enough.”

“Her secret is vitality,” said one observer of her free-range encounters. “It is all most tangible. It reaches out to you, it takes possession of you.” People felt it in the steadiness of her hand – the handshake firm, the hand itself surprisingly soft in one’s grasp. “She has a handclasp that means something,” they said in Wisconsin, “a handclasp into which she injects a fine impersonal warmth, a vitality.” A man in the Bronx, Victor Rodriguez, once shook her hand, and decades later could “still feel her warmth in my palm.” Another New Yorker, a speakeasy owner, gave the credit for “changing the country back into the United States” not to FDR but to Mrs. Roosevelt. “She was the genius of that family.” Because of her, recalled “Broadway Tony” Soma, “we are adventurous today.”

“It wasn’t the handshake,” expanded one Democratic party leader. “One of Mrs. Roosevelt’s special traits was that of looking at a person straight in the eye. It was a human spark in her eyes – the recognition of nobility of each individual, black, white, red, yellow, young, old, men, women – that established a bond which was a very personal experience for all who met her, even fleetingly.”

Her stride “rapid and lengthy,” as the Secret Service described it, she swept into places like Muncie, Indiana, her manner unruffled and unhurried as she met with the press in her hotel room upon arrival. Later, upon discovering that two reporters from the high school paper had been made to wait in the lobby, she gave the girls an “exclusive” for the Munsonian, which captivated the old pros from the wire services, who never quite believed that anyone could have that much goodwill.

For some townsfolk, her enormous corsages and sentimental jewelry touched a sympathetic chord, as did her slim hands, the fingers tapered like those of a glove model, her “perfect filbert-shaped” fingernails the pride of her official portrait painter. Others were charmed by the crinkles that appeared under her eyes when the 4-H Club presented her with a large white goose for a pat on the head or the high schoolers offered her an invitation to speak at their graduation or the Boys Club boys sang “How Do You Do, Mrs. Roosevelt” as she nodded her head in time to the music. When they launched into the Caisson Song, with its swinging “Over hill, over dale” opening lines, they faltered a bit, but she urged them on with an eye-crinkling smile, topping the applause at the end with her benediction, “That’s swell, that’s really fine singing.”

Afterward, the men handed her copies of a Portland newspaper carrying her picture on the front page, the caption nominating her for vice president. The women, who only that morning at breakfast had been appalled to learn that Mrs. Roosevelt had already finished her Christmas shopping in October, were surprised and comforted by her easy laughter and neighborly way of chatting on street corners. By four o’clock in the afternoon, when they found her dispatching her daily column from their local Western Union office, they wondered when she had found the time to write such a thing, and asked, “Anything in it about Muncie?”

“Yes,” she replied, and they beamed.

Excerpted from “Eleanor” by David Michaelis. Copyright © 2020 by David Michaelis. Published by Simon & Schuster. All rights reserved.

For more info:

- “Eleanor” by David Michaelis (Simon & Schuster), in Hardcover, eBook and Audio formats, available via Amazondavidmichaelis.com