Astronomers have previously spotted glowing auroras surrounding planets, as well as Jupiter’s moons — but now, for the first time, they’ve found the dancing light show on a comet.

Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko — Chury for short — which was studied by the Rosetta comet hunter from 2014 to 2016, appears to have its own far-ultraviolet aurora, NASA said Monday. It marks the first time such electromagnetic emissions have been detected on a celestial object that is not a planet or moon, scientists wrote in a new study in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Aurora, known as the northern and southern lights, are created on Earth from electrically charged particles zooming from the sun to the upper atmosphere — generating a stunning multicolored glow in the sky. Jupiter and some of its moons, along with Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and Mars have all experienced their own version of the spectacular light show.

But Chury marks the first time astronomers have documented the phenomenon in a comet.

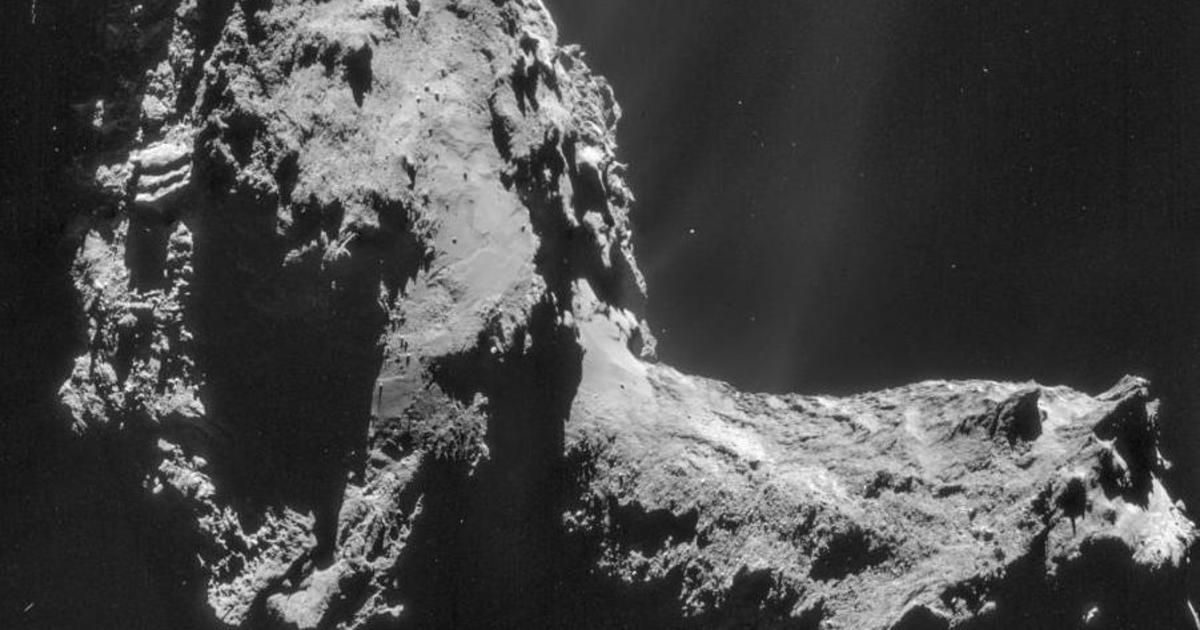

This animation comprises 24 montages based on images acquired by the navigation camera on the European Space Agency’s Rosetta spacecraft orbiting Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko between Nov. 19 and Dec. 3, 2014.

ESA/Rosetta/NAVCAM

According to NASA, Rosetta, which launched in 2004, was the most traveled and accomplished comet hunter in the space program. It studied Chury’s gas, dust and plasma environment, taking some pretty epic photos along the way, until its mission came to a successful end in September 2016 — when it deliberately and dramatically crash-landed into the comet.

When studying data from the mission, scientists originally interpreted the aurora as “dayglow” or “nightglow,” which occurs when photons of light interact with gas from the comet’s nucleus, known as the coma. But a closer look at the data has revealed something much more unique.

“The glow surrounding 67P/C-G is one of a kind,” lead author Marina Galand, from Imperial College London, said in a news release. “By linking data from numerous Rosetta instruments, we were able to get a better picture of what was going on. This enabled us to unambiguously identify how 67P/C-G’s ultraviolet atomic emissions form.”

A view of the Northern Lights on Earth.

“Rosetta is the first mission to observe an ultraviolet aurora at a comet,” Matt Taylor, ESA project scientist, said in a statement. “Auroras are inherently exciting — and this excitement is even greater when we see one somewhere new, or with new characteristics”.

In this case, the electrons streaming out from the sun are interacting with the comet’s gases to break apart water and other molecules. The result is a far-ultraviolet light that is invisible to the naked eye.

“Since this process is very high energy, the resulting glow is also highly energized and therefore in the ultraviolet range, which is invisible to the human eye,” said co-author Martin Rubin, from the University of Bern Physics Institute.

Understanding the comet’s aurora will help scientists better understand weather, specifically solar wind, throughout the solar system in order to protect future satellites and spacecraft — and even astronauts traveling to the moon and Mars. Scientists plan to continue digging through data from the Rosetta mission for even more hidden treasures.

“Rosetta is the gift that keeps on giving,” said co-author Paul Feldman, from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. “The treasure trove of data it returned over its two-year visit to the comet have allowed us to rewrite the book on these most exotic inhabitants of our solar system — and by all accounts, there is much more to come.”