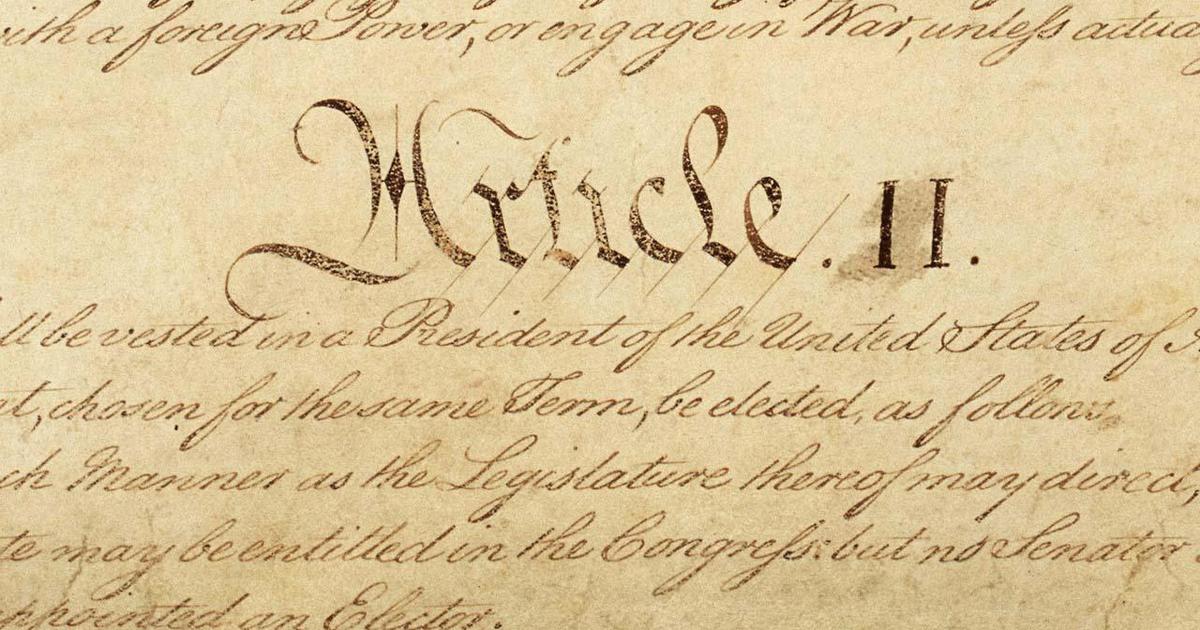

The power of the president is enormous – and this president is not bashful in describing powers that go well beyond simple declarations.

In April, when discussing guidelines to be issued to governors about reopening states during the coronavirus pandemic, President Donald Trump said, “When somebody is the President of the United States, the authority is total, and that’s the way it’s got to be – it’s total.”

There are, it’s true, some restraints on most presidential authority, but those might not apply to all the president’s powers.

As Mr. Trump stated in March, “I have the right to do a lot of things that people don’t even know about.”

We can’t know for sure, but what the president appears to have been referring to are his presidential emergency action documents, often referred to as PEADs.

“Even though I’ve had security clearances for the better part of 50 years and been in and out of national security matters during that half-century, I had never heard of these ‘secret powers,'” said former Senator Gary Hart.

“Sunday Morning” special contributor Ted Koppel asked, “Do you know what they are, now that you’ve heard of them?”

“Only vaguely, due to research done at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University Law School,” Hart said. “What these secret powers are, apparently, based on the research, is suspension of the Constitution, basically. And that’s what’s worrying, particularly on the eve of a national election.”

The Brennan Center research that Senator Hart referred to has been spearheaded by Elizabeth Goitein, the co-director of its national security program, and a contributing writer at The Atlantic.

“These are essentially presidential orders that are drafted in anticipation of a range of hypothetical, worst-case scenarios,” Goitein said.

- The alarming scope of the president’s emergency powers (“The Atlantic)

Koppel asked, “Several times during his administration, President Trump has made allusions to secret powers that he has that we don’t know about. Is he making that up?”

“Well, not exactly,” Goitein replied. “And what’s alarming about that is that no one really knows what the limits of those claimed authorities might be, because they are often developed and kept in secret.”

Goitein says what little we do know about PEADs comes from references to them in other documents, some of which are now declassified.

“They originated in the Eisenhower administration as part of an effort to try to plan for a potential Soviet nuclear attack,” Goitein said. “But since then, they’ve expanded to address other types of emergencies as well. No presidential emergency action document has even been released, or even leaked. Not even Congress has access to them, which is really pretty extraordinary when you consider that even the most highly-classified covert military and intelligence operations have to be reported to at least eight Members of Congress, the ‘Gang of Eight.'”

“You’re saying they are not consulting with Congress?” Koppel asked.

“Exactly,” said Goitein. “Congress is not aware of these documents, and from public sources we know that at least in the past these documents have purported to do things that are not permitted by the Constitution – things like martial law and the suspension of habeas corpus and the roundup and detention of people not suspected of any crime.”

A 1967 memo from William Cornelius Sullivan of the FBI alludes to a PEAD which authorizes the suspension of habeas corpus. “This is a drastic program set up under the assumption that drastic steps will be necessary to protect the national security of this country so that efforts can be made to remove from circulation individuals determined to be potentially dangerous to the national defense and public safety of the United States by engaging in espionage, sabotage and/or subversion in the event an attack is launched against this country,” Sullivan wrote.

Brennan Center for Justice

Hart said, “The reason these documents are secret is, for 11 administrations, people in power did not want to frighten the American people, or to demonstrate what might happen to their constitutional rights and liberties.

“Every administration, including Democratic administrations, has revised and updated these powers. I started contacting friends of mine, of both parties, who had been in senior positions, and I got two responses, or one response which is, ‘I’ve never heard of these powers’ (and these are people in senior cabinet positions), or, I got no response at all. And it was the no-response-at-all from people I knew that began to worry me. Because there not only is secrecy around these powers, there is mystery around the secrecy.”

“I think I know as much about the PEADs as any other American citizen, which is almost nothing at all,” said David Cole, national legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union – and he is concerned about the vast array of presidential emergency powers that we do know about.

Under the National Emergencies Act of 1976 alone, the president can declare a national emergency just by signing a proclamation.

Cole said, “We’ve got a president who, in his first week in office, essentially declared an emergency to ban Muslims from coming into the country. More recently, [he] declared a widely understood to be a fake emergency in order to build a border wall when Congress told him they would not give him the funds to create a border wall.

“And most recently, [he] has declared that he may need to delay the election, which would be an emergency authority that doesn’t even exist. So, I think you have to be very concerned.”

Which brings us back to those mysterious Presidential Emergency Action Documents:

John Yoo is a law professor at the University of California, Berkeley. While serving at the Justice Department after 9/11, Yoo drafted the memo that justified the use of “enhanced interrogation” of terrorism suspects.

Yoo was asked by Koppel, “Just to reassure our viewers a little bit, John, you’ve seen these PEADs?”

“I am not allowed to say whether I have or not,” he laughed.

“Let me put it this way: You were at the Justice Department. Presumably the Justice Department would’ve had to deal with these PEADs if a president wanted to implement one?”

“Yes, that’s fair to say,” Yoo replied. “The Justice Department and the office I worked in would review the legality of the PEADs because they would draw on presidential powers and Congressional powers delegated to them.”

Just a couple of weeks ago, Yoo was at the White House discussing executive power with President Trump.

“‘Cause you never know what the emergency is gonna be,” said Yoo. “So, these PEADs and similar contingency planning documents, when we look back historically at them, sometimes they seem comic.”

“The notion that there are executive powers based on something that has never been vetted by Congress, giving the president almost limitless powers to do what he needs to do in the event of a crisis, that’s not funny to me; that’s scary,” Koppel said.

“Oh, forgive me. I don’t mean this whole question is comic,” Yoo said. “And you are right, Ted. There’s dangers to that, and we’ve seen in our history where presidents have gone too far. I guess there’s a balance, and I guess the founders, they balanced in favor of giving the president that kind of ability to face emergencies, even understanding that a badly-intentioned president might abuse those powers.”

Goitein said, “These PEADs undergo periodic revision. And we know that the Department of Justice is in the middle of one of these periodic reviews and revisions. So, we have to imagine what the Trump administration might be doing with these documents and what authorities this administration might be trying to give itself.”

Yoo said, “That’s why the framers created the presidency, was because it could act quickly. I would want President Obama or President Biden to have the power to respond quickly to a hurricane or a terrorist attack, just as I would want President Trump to.”

“That’s fairly benign, John,” said Koppel. “But what if what the president was planning to do was the suspension of habeas corpus? How would you feel about it then?”

“I’d be the first to admit that, in emergencies, the executive branch can make mistakes, and that’s sometimes the price of swift action,” Yoo replied. “Congress is more likely to get things right. The founders thought that. But Congress is too large and too slow to act decisively.”

Having said that, Yoo would be comfortable giving a few select Members of Congress classified access to the secret PEADs.

Gary Hart doesn’t think that goes far enough: “I want them public, because they affect the freedom and liberty and rights of every American citizen,” he said. “I can’t say it any better. This is a blueprint for dictatorship. Now, I think the more attention it gets, the less likely those in power are going to use them.”

Koppel said, “We have so much publicity, Senator Hart, we have so many different voices being raised in anger, in outrage, in fury, I’m not sure what a few more voices raising an issue like this, what impact that’s going to have.”

Hart replied, “This goes to the core of our country and our founding. And if there is what amounts to the capability to suspend our Constitution, that’s not just another issue. That’s serious. Keep in mind, the current, incumbent president has declared seven national emergencies. And he has stated repeatedly that he has more power than most people know about.”

“And you find that frightening?” asked Koppel.

“I will not reverse the question,” Hart replied.

For more info:

- Brennan Center for Justice, New York UniversityElizabeth Goitein, The Atlantic“The Republic of Conscience” by Gary Hart (Blue Rider Press), in Trade Paperback and eBook formats, available via AmazonAmerican Civil Liberties UnionJohn Yoo, Berkeley Law, UC Berkeley“Defender in Chief: Donald Trump’s Fight for Presidential Power” by John Yoo (All Points Books), in Hardcover, eBook and Audio formats, available via Amazon

Story produced by Deirdre Cohen. Editor: Ed Givnish.