Victoria Wood ’s wit and warmth made her one of the country’s best-loved comedians and a true national treasure – but behind the laughter lay the trauma of a tough childhood.

Here an exclusive extract from Let’s Do It: The Authorised Biography of Victoria Wood, by Jasper Rees, tells how the comedian, who died of cancer aged 62 in 2016, was shaped by her early life…

Victoria Wood had an adoring female audience long before she drew her first breath.

“The baby’s kicking”, her expectant mother would say. “Come and put your hand on my tummy.”

Victoria’s sisters Penelope, seven, and Rosalind, two-and-three-quarters, would feel their unborn sibling beating out a rhythm with her feet. Their brother Christopher, who was 12, may have been less engrossed by another arrival.

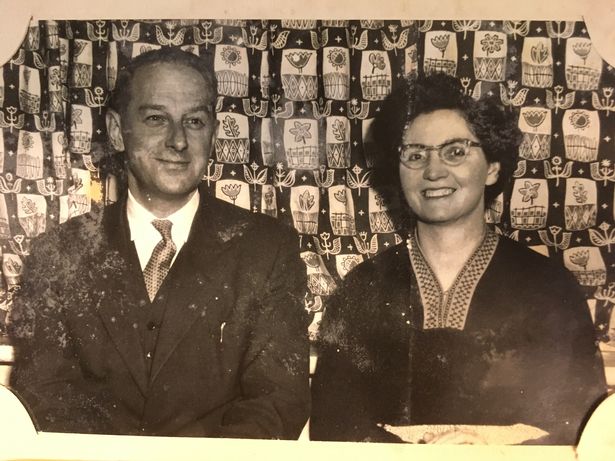

After Helen Wood gave birth in a nursing home in Prestwich on the northerly outskirts of Manchester, Stanley Wood’s diary entry recorded the birth of “Victoria Wood, 7lbs 12ozs born @ 8pm”.

The proud father pronounced her “a lovely baby in every way”.

Sadly, this attention was not to last. Fiercely private, Victoria rarely spoke of what appears to have become neglect in her later childhood.

But beneath her outgoing stage persona, their actions had created deep-seated feelings of abandonment, leaving her crippled with shyness and battling with self-loathing for much of her adult life.

It was in 1958, when Victoria was five, that family life began to disintegrate.

The Wood family moved from their suburban home in Bury to Birtle Edge House, an isolated former children’s home overlooking the Rossendale Valley.

The isolation was exactly what appealed to Helen. “My mother couldn’t be doing with neighbours and gossip and suburban life,” said Victoria. “Nobody came to tea at all.”

Helen decided to return to education to get the qualifications she had missed out on, having had to leave school young, and she became consumed in her own life.

Victoria later reflected that she “loved having babies but didn’t like children very much”. Stanley, an insurance salesman and part-time writer and musician, struggled to connect with his children.

The family started to lead cellular lives – “like battery hens”, Victoria said. When they did meet they would do so on a provisional basis, standing in a group to talk and josh, but never sitting.

Stanley’s habit was to natter in doorways, as if always keeping open the option of a getaway. “My father was lovely in a way,” Victoria would say, “but not easy to talk to. He didn’t hurt one, he just didn’t connect.”

Victoria was once asked if the family had rows. She said: “Didn’t talk enough to have rows!”

Helen, a keen dressmaker, struggled to keep her daughters looking neat and clean. She was summoned for a chat with the headmaster about the girls’ appearance. “We were both very dirty and obviously looked neglected,” says Rosalind.

This was a product of Helen’s struggles with depression, during bouts of which she would give up on cooking and washing. “Sometimes you’d go through the sitting room and she’d be sitting in a slump,” says Penelope.

Anne Sweeney was one of the few school friends to visit Victoria at the house, and found it “rambling and neglected” but “thrillingly bohemian”. Most unusually “there didn’t seem to be anybody there saying, ‘Do this, do that.’ Victoria never used to talk about her parents at all”.

Victoria catered for herself and, says Anne, ended up “eating quite badly”. Then Helen left.

Victoria’s friend, actress Julie Walters, said the comic’s 1994 TV film Pat and Margaret was inspired by her mum.

“She said her mum left when she was about 11,” she said. “When she left Victoria went into chaos. She felt abandoned and couldn’t function very well.”

When Victoria was 12, Helen took her to the GP and asked for a pills to suppress both their appetites.

Penelope says: “Mum wasn’t very nice to Vicky really. I think she found it hard that she was so scruffy and lazy and sleeping and reading all the time. I think Vicky might have been hard going for Mum.”

The fact Victoria’s sisters were tall and slim made it harder for her. “I felt they were better at everything,” she said.

“I thought if you were thin you were happy, if you had a boyfriend you’d be happy, if you had a different family and lived in a nice, clean semi, you’d be happy.”

Dieting became a leitmotif of Victoria’s comedy for 30 years.

She sang about it as a gloomy student in Nobody Loves You When You’re Down and Fat, and it was a preoccupation in the early sketches she wrote for herself and Julie.

“This is a boutique, not the elephant house,” says Julie as a sales assistant in 1981’s Wood and Walters, aiming a sub-machine gun at Victoria.

Her trick was to mention her weight before anyone else did. In As Seen on TV in 1985 she said: “You could dial my measurements and get through to the Midland Bank, Bulawayo.”

As her career progressed she began to fight back. A section in her 1993 stand-up show angrily confronted the slimming industry.

Through Dolly and Jean in Dinnerladies in the late 90s she poked fun at women bickering about weight.

Finally, in her last stand-up tour At It Again in 2001, she publicly admitted to an eating disorder.

She said: “If you’ve got an eating disorder, eating replaces almost any need you have.

“It covers up your feelings. It puts up a barrier between you and people because people are scary but food’s not scary…”

She confronted her demons in her hard-hitting 2004 documentary, Victoria Wood’s Big Fat Documentary.

She ended with the rallying cry: “If life deals you a pile of manure, they say you should grow roses. So I say, if life gives you a belly, go dancing.”

- Extracted by Emily Retter from Let’s Do It: The Authorised Biography of Victoria Wood by Jasper Rees published by Trapeze, £20. Also available in ebook and audiobook. Text copyright © Jasper Rees 2020.