The 1968 Fair Housing Act outlawed redlining nationwide. But the disastrous effects of the discriminatory practice are still contributing to today’s wealth gap between Black and White Americans.

“I think you see it in every city in America,” Atlanta councilman Amir Farokhi told CBS News’ Michelle Miller. “This is where the basis of segregated neighborhoods remains to this day.”

Farokhi represents a divided district in Atlanta — half the area is enjoying the bloom of reinvestment, while the other is still blighted.

“We can draw a line kind of northwest to southeast, and most of the neighborhoods above that line are predominantly White and most beneath it are predominantly Black,” he said. “You are still living with generational divide and the wealth gap that happens because of that.”

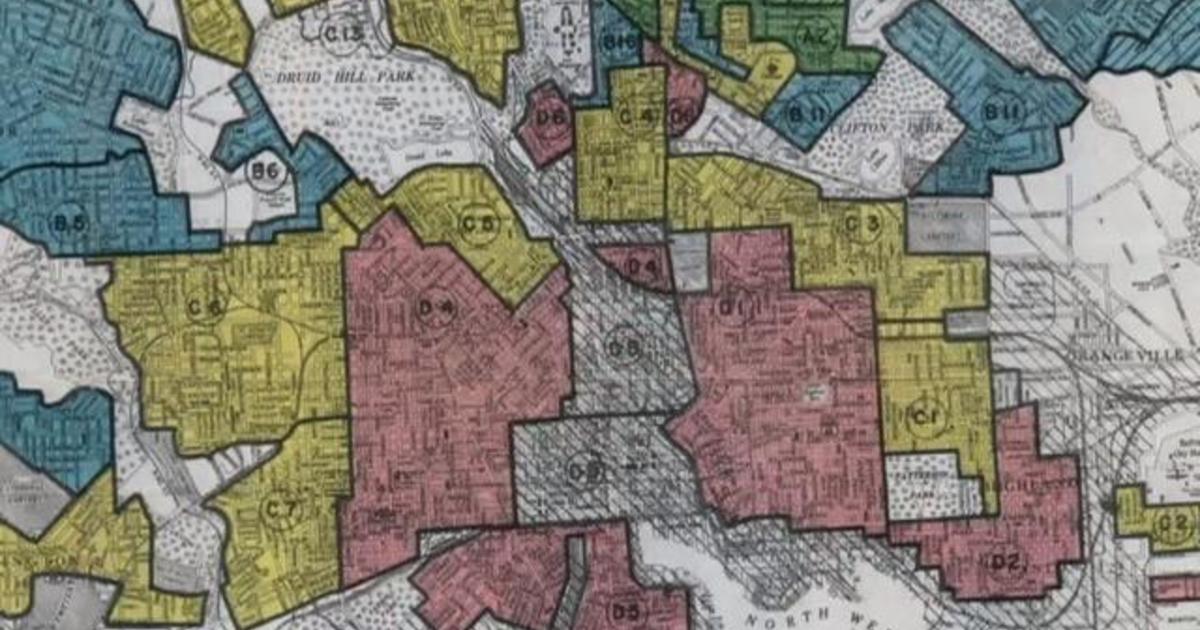

The federal government began the practice of redlining in the 1930s, outlining areas deemed “hazardous” — often home to sizable Black, minority and immigrant populations. Based on that, mortgage lenders would deny loans to low-income minorities in those neighborhoods, causing disinvestment and placing home ownership out of reach for people of color.

Atlanta resident Kimberly Alexander said her family saw the inequity unfold firsthand along the city’s Auburn Avenue.

“It was everything,” she said of the predominantly-Black area. “It was Black excellence. It was Black commerce.”

In its heyday a century ago, Alexander’s family business was a fixture there, until the area — and the country itself — began changing.

“There was a period of time after desegregation where businesses shuttered and left because they had opportunity elsewhere,” Alexander said. “And some people thought the grass was greener on the other side. And so unfortunately that left a lot of buildings plighted and the area plighted.”

Thus, the community was redlined.

Many neighborhoods that were redlined like Auburn Avenue, deemed “hazardous,” are still more likely than others to consist of lower-income, minority residents.

In 2016, the median net worth of Black households was about $17,000. The median net worth of White households was $171,000 — about ten times more.

Atlanta officials have pushed projects like “Invest Atlanta” to revitalize distressed areas, and other community leaders are stepping up to help close the gap left by redlining.

“The houses that you see in this neighborhood were either vacant lots or just dilapidated,” Historic District Development Corporation head Chenee Joseph said. “And so within 40 years HDDC alone has built or re-habbed about 121 single family homes. We’ve built about 500 units.”

The grassroots organization was founded by Coretta Scott King and other civil rights leaders to preserve the nearby Martin Luther King, Jr. historic corridor. In addition to revitalizing family homes, HDDC has also rehabilitated 40,000 square feet of commercial space.

However, the growth came with its own challenges — a majority of affordable housing in the area is owned by nonprofits and churches, so the HDDC cannot easily profit off its investments.

“We’ve basically had to create something out of nothing,” Joseph said. “To be able to do that almost single-handedly is an accomplishment that we don’t take lightly.”

The group is looking to expand its mission in the near future, as Joseph demonstrated with plans of future Auburn Avenue projects.

“You’re looking at about half a billion dollars of redevelopment,” she said.

She said the plan would be a good investment, despite the hefty sum.

“You’re working with stakeholders that already own their properties. So you’re not having to deal with acquisition. But more importantly, what you’re doing is you’re reinvesting into your community that’s going to continue to prosper time and time again,” she explained.

Despite the practice being illegal, Black loan applicants are still turned away by banks at a higher rate than White applicants. The widespread use of redlining has allowed generations of White Americans to build wealth through equity in homes and businesses, further widening a wealth gap African Americans have yet to rebound from.

Another person trying to reverse the trend is Chicago native and real estate developer Lamell McMorris, who is working to revitalize neighborhoods without completely gentrifying them or pricing out long-term residents — he calls the practice “greenlining.”

“I want to make greenlining about neighborhood reinvestment and neighborhood redevelopment,” McMorris said. “I’m going to try to make a difference here.”

In June, McMorris’ firm Greenlining Realty USA partnered with a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit to build and rehabilitate residential properties in Chicago’s Woodlawn neighborhood.

He acquired vacant, abandoned and tax delinquent properties and sells them at below market rates to buyers who must be community-based developers. The buyers then rehabilitate the properties and sell them to prospective homeowners.

“My goal is to be a resource and to be a catalyst and spur investment… like dropping a pebble and watching a ripple effect,” he said.